Unspoken Things

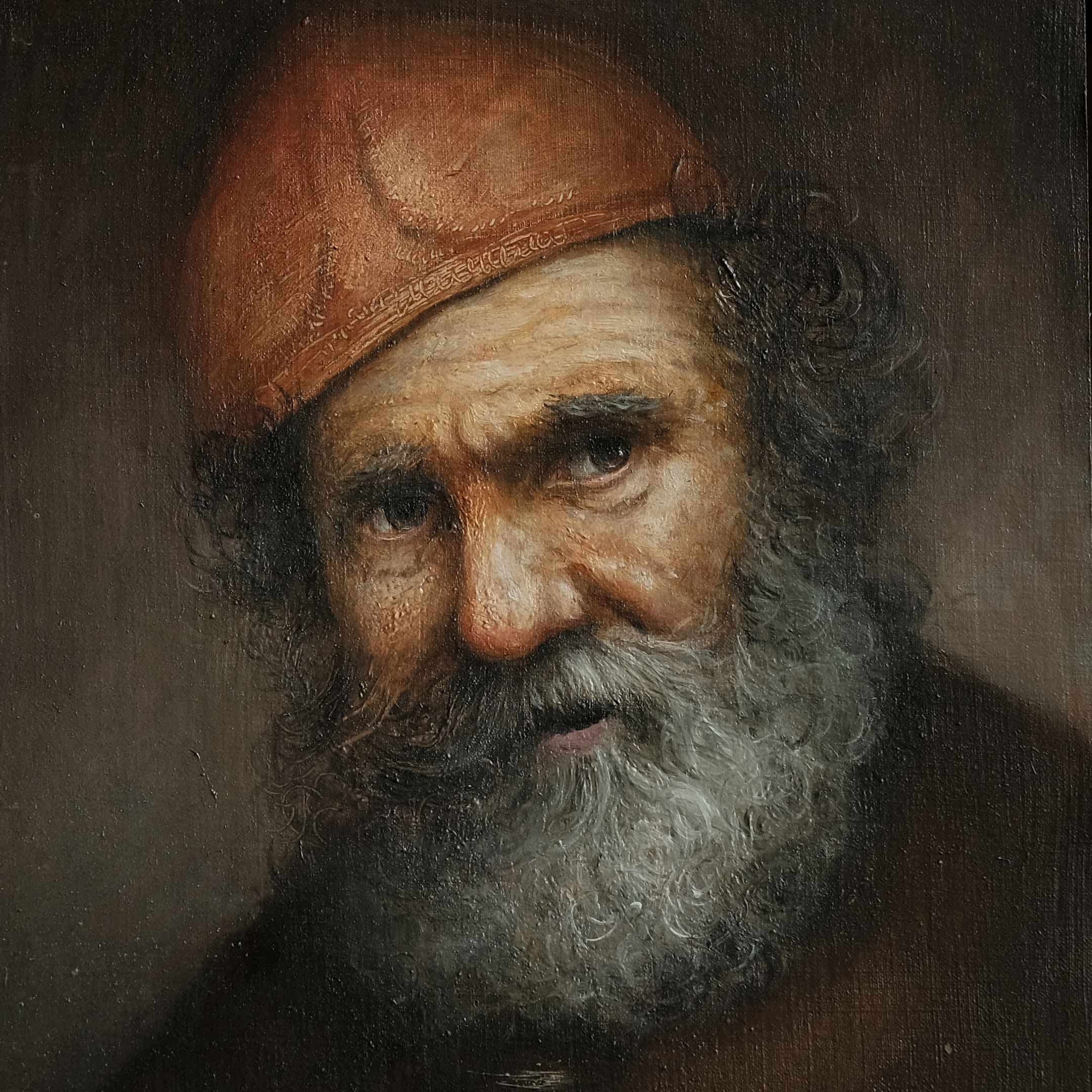

Oil on paper study – traditional Old Masters technique with natural pigments and lead-based whites

The genius of this portrait lies in its restraint. It does not shout; it whispers. The man’s expression is not overtly theatrical, but emotionally loaded. There is a subtle irony in the eyes, a questioning glance that implies both skepticism and warmth. We are invited to wonder: what has he just heard? What thought is forming behind that furrowed brow? What truth is he weighing?

Unspoken Things Oil on Paper, Handmade Pigments and Dutch Lead White — Old Masters Technique

The subject, likely a Jewish elder, stands as a symbol of resilience and introspective strength. He is not idealized, but profoundly human. His features are carved by time, marked by the evidence of a long life lived — and endured. His mouth, slightly ajar, suggests the trace of a smile or a thought withheld. The tension in the expression lies in this ambiguity — it is a portrait of emotion not yet spoken.

Special attention was given to the creation of the lead white pigment — a crucial component of classical painting — which was made personally by the artist following the Dutch stack process, a 17th-century method historically used by painters such as Rembrandt and Vermeer. This method yields a warm, dense white with unique handling properties and subtle translucency, allowing for the lifelike rendering of skin tones and light.

Multiple transparent and semi-transparent layers

Technique and Materials

This painting was executed with the layered technique of the Old Masters, where form is slowly built up through successive glazes and scumbles, resulting in an image of profound depth and material richness. The artist began with a carefully prepared ground and underpainting, establishing form and value before proceeding with semi-transparent color layers rich in oil and resin.

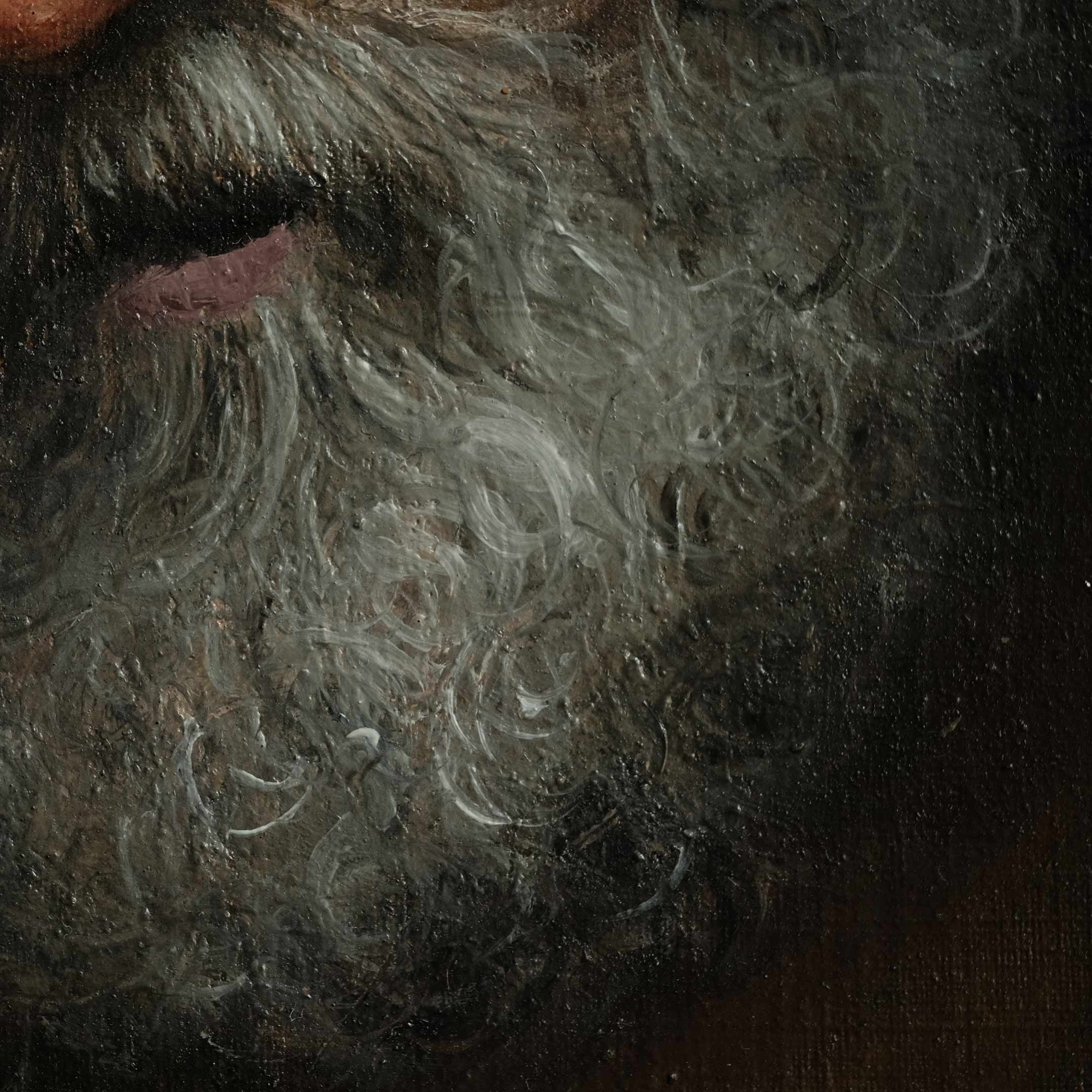

The highlights and modulations of skin and beard are rendered with lead white, a pigment that has no equal in its subtle warmth and luminosity. Its capacity to reflect light from within the paint layer allows for an uncanny realism in flesh tones — a “living surface” quality that cannot be achieved with modern titanium whites.

Areas of warm undertone — particularly visible in the cap and cheeks — employ lead-tin yellow, an ancient pigment that brings a soft, honeyed brightness to the palette. The beard, meanwhile, is layered in grays mixed from natural black, umber, and hand-ground whites, carefully glazed to maintain the texture of individual strands.

Expression and Interpretation

The genius of this portrait lies in its restraint. It does not shout; it whispers. The man’s expression is not overtly theatrical, but emotionally loaded. There is a subtle irony in the eyes, a questioning glance that implies both skepticism and warmth. We are invited to wonder: what has he just heard? What thought is forming behind that furrowed brow? What truth is he weighing?

This is not a portrait of a single moment, but of a lifetime condensed into a single look. The soft red of his cap, worn and functional, becomes almost sacred in its simplicity — a quiet badge of identity and endurance. He is a man from another time, yet entirely familiar. We recognize him because we have seen versions of him in our own families, in our elders, in ourselves.

His silence is not emptiness — it is watchfulness. And it is this tension — between speech and silence, light and shadow, past and present — that makes the painting so alive.